An Introduction To Microphone Types, Uses, and Techniques

Author: Kieron Seth#

Published 1st June 2011

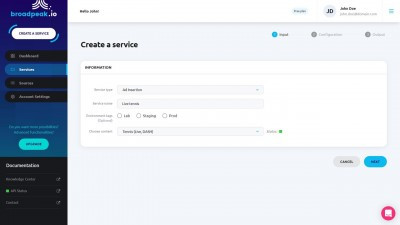

Almost everyone knows what a microphone is, but far fewer people know how they actually work and how to get the best out of the various types available. Pieter Schillebeeckx, Chief Designer at UK microphone manufacturer SoundField, fills in some basics.

As technology has become easier to use, cheaper and more portable, it's become more popular. Early Victorian photographers were few in number and tended to be members of the aristocracy, mainly because few people had the free time or the money to invest in the vast arrays of clunky technology and the expensive chemicals that were required. But today, everyone can aspire to be another Rankin or David Bailey, using nothing more commonplace than a mobile phone.

Inevitably, as technology becomes more accessible, and more people get involved, so the numbers of users that don't understand the underlying technology increases steeply. There's plenty of modern gadgets we use every day without knowing how they tick: we're all perfectly capable of firing up Google and making cellular phone calls without understanding the finer points of how search engines or 4G mobiles work. And with the rise of mobile phones, there's an older piece of technology which most people use every day without ever stopping to think how it works. If you shoot video at any creative level, you depend on it far more than you realise: the humble microphone.

Although many TV-Bay readers might think of a microphone as nothing more than an inexplicably clever gadget behind a grille that records your voice, there are many types, and many ways to use them that can enhance your productions. As with all creative endeavours, developing a bit of technique can make you a much more proficient master of your craft

So what is a microphone? It's a device that captures and converts the wave-like variations in atmospheric pressure that we hear as sound. Most microphones convert these continuously varying sound waves into fluctuating voltages which can then be amplified, recorded or broadcast. Of course, human beings can't listen to voltages, so the final stage in this process is always the conversion of the voltage back to continually varying sound waves by loudspeakers, so that our ears can hear the results. Because there are more ways than one to convert a sound wave into a voltage, so there are many different microphone designs — and some are better suited to certain jobs than others.

DYNAMIC MICROPHONES

If you remember any physics from your school days, you might recall that moving a coil of wire in a magnetic field produces a current and voltage in the wire — and this fact led, in the early 20th century, to the invention of the dynamic microphone, one of the most widespread types. At the business end of a dynamic mic (usually known as the 'capsule'), a thin diaphragm is connected to a coil of wire suspended in a magnetic field. When sound reaches the mic's diaphragm, the vibrations cause the diaphragm to move, the connected coil also moves, and a small current and voltage are induced in the wire, the size of which fluctuates with the strength of the original vibrations. This signal can then be amplified, recorded or broadcast.

Despite the many refinements to their design over the years, dynamic microphones are fairly inefficient, because sound vibrations have to be relatively powerful in order to move a diaphragm attached to a coil of wire in the first place. Treble frequencies, in particular, are picked up less well by dynamics, although they do a good job of capturing bass sounds. On the plus side, however, dynamic mics tend to be very affordable and hard-wearing, which is one reason why they are so widely used, particularly to capture live music. Most people's clichd ideas of what a microphone looks like — a mesh- or fuzz-covered ball on a stick — derive from famous dynamic mic designs, like the everlasting Shure SM58. Designed in the mid-1960s, this mic is still popular and in production today.

CONDENSER & ELECTRET MICROPHONES

Condenser microphones are far more elegant and accurate, and much better at picking up high frequencies than dynamic mics, but they are also rather more expensive and delicate than dynamic models. In this design, the capsule is completely different to that of a dynamic mic: the diaphragm, usually made of a light polymer material covered with an extremely thin coating of gold to make it electrically conductive, forms one half of a electrical element known as a capacitor (a simple electrical component which holds a electric charge). The other half of the capacitor is an immobile fixed conductive element known as the backplate. A constant charge is applied across the capacitor, but as sound waves reach the diaphragm and move it slightly, the distance between the moving diaphragm and the fixed backplate varies, and a fluctuating voltage is produced which faithfully tracks the movement of the diaphragm. The name ‘condenser mic’ has stuck, as capacitors used to be known as condensers in the days when these mics were first invented. They’re also often called capacitor mics in technical circles. Some of the world's best and most expensive mics, like Neumann’s U87, are condenser designs.

Aside from their relative cost, true condensers are also more demanding than dynamic mics, as they require a constant electrical voltage to be applied to them in order to work (to produce the constant charge across the capacitor). In broadcast and recording studios, this so-called 'phantom power' is conveniently supplied down the microphone cable from a mixing console or separate phantom power source. When working 'in the field', true condenser mics have to be fitted with batteries to provide the required charge.

There is a way around the requirement for phantom power, and it is to build a capacitor microphone which contains a permanently charged element. Such condensers are also known as electret microphones (an electret is an electrical element with a permanent charge). Many of the built-in microphones in video cameras are electret condenser microphones, as they form a good compromise between cost and quality.

Although there are many other types of microphone, you'll find that dynamics, condensers and electrets are the main ones used in video production.

PICKUP PATTERNS & THEIR USES

Going beyond the basic types of microphone, different microphone capsule designs are sensitive to the sound they pick up around them in different ways. A microphone capsule that picks up sound all around it equally well is known as an omnidirectional microphone (or omni for short). If you plot the sensitivity of an omni mic around its capsule, the resulting graph of directional sensitivity, known as a 'pickup pattern' is almost circular, but there are many other types of microphone capsule, named after the way their pickup pattern plots look on paper, as you can see in the plots printed in this article. These include 'cardioid' capsules (which look like an upside-down heart, as the mic is much less sensitive to sounds received from the rear) and 'figure of eight' types (no prizes for guessing the shape of this one's pickup pattern - it picks up sound in front and from the back, but is very insensitive to sounds received from the side or above).

The directionality of these different types of pickup pattern can be very useful when planning a video shoot. To capture the entire ambience of a particular location, for example, an omnidirectional mic would be a good idea. But to pick up a very specific sound source — say a particular presenter or actor in a scene — a directional mic like a cardioid, or still more directional types, like the supercardioid or hypercardioid, are better solutions.

Imagine you're filming a scene in a railway station. An omni microphone will do an excellent job of capturing the hubbub of the crowds coming and going from all angles, the sounds of trains arriving and leaving, and tannoy announcements, creating a convincing station ambience. However, the omni mic will pick up all of this noise just as well as your presenter or actor speaking directly in front of the camera. To pick up audio from just the sound sources directly in front of the camera requires a mic with a much more directional pickup pattern, which is why the shotgun microphones built into video cameras tend to be hypercardioids. These have one of the most selective pickup patterns of all, with great sensitivity to sounds directly in front, some sensitivity to the rear, and very little to the sides. To get the best from location sound, many video sound engineers record their audio in different takes, capturing ambience with an omni mic, then recording any dialogue in a separate pass with more directional mics. The multiple recordings can then be mixed later in post-production to give a convincing sense of the sound on location, but with comprehensible dialogue. Experienced location recording engineers, if they have sufficient time, often make several different recordings at any given site using various types of microphone.

Originally, it was solely the physical design of a mic capsule that dictated its pickup pattern. Some manufacturers created mics with selectable pickup patterns by including a physical baffle that could be adjusted to close off or open up the mic capsule, making it more or less sensitive. Another way to offer all pickup patterns with a single mic was to create modular microphones with a single common body and switchable heads. Modular mics, such as Sennheiser's MKH8000 range, are still popular for location recording today. although with modern technology it is now possible to vary pickup patterns electronically. Some mics, including those made by our own company, SoundField, offer continuously variable patterns from omni at one extreme, varying through cardioid to supercardioid, hypercardioid, and figure-of-eight at the other.

TECHNIQUE, AUDIO FORMATS & ACCESSORIES

Making audio recordings with the mics built in to your video cameras is easy, but as soon as you progress beyond that stage, there are many different ways to achieve your ends. It’s easy to improve on the quality of built-in camera mics with external microphones, and if they are mounted away from the camera, they won't suffer from camera noise or vibration. Single-mic recordings with external mics are fairly straightforward, but some location sound recordists prefer to use multiple microphones simultaneously, in which case some kind of audio mixer is also required to plug the various mics into and to balance their relative levels. An external audio recorder may also be useful for audio capture from multiple microphones, as there may not be a way to recording the output of several mics on your video camera simultaneously. Of course, if you work on location, any mixers or recorders you use have to be both reasonably portable and capable of being battery-powered, although plenty of products fit this description.

There's also the question of whether to make your recordings in mono (one audio channel), stereo (two channels), or surround sound (using multiple channels, four or more) on location, or whether to make separate recordings on location which can be mixed into stereo or surround mixes in post-production. Mono recordings are sufficient for video podcasts, quick radio or budget TV news broadcasts, stereo is the widely accepted standard for TV worldwide, and surround is a developing format, standard in cinemas and increasingly, in high-definition TV services. The golden rule is to consider what your production's audio requirements are: the soundtrack for a YouTube video could be mono, but this would be unacceptable for a cinema production, and the requirements of a TV news report or training video will be different again.

It's not essential to use multiple microphones and a mixer to create stereo or multi-channel soundtracks, and this is just as well, as whole books have been written on stereo and multi-channel microphone techniques, and not all of these techniques produce audio that is suitable for broadcast or film sound. Individual stereo and multi-channel microphones are available, although they tend to be more expensive than their mono counterparts. SoundField microphones even allow the user to choose the exact output format from mono through stereo to surround, after the event and all from a single microphone. These have found favour with international broadcasters, who like their soundtrack to be in surround sound to accompany their high-definition transmissions, but also need it to be compatible with stereo for standard definition broadcast.

GET MIKING!

This article is designed to do no more than whet your appetite to find out more about basic microphone types and techniques. The best way to progress from here is to keep reading articles on location sound recording in magazines like TV-Bay or on-line, attend courses on the subject (of which the UK has plenty), and, of course, to get out there and experiment with video sound yourself!