The more I look into it the more scary 3D is. Researching for 3D Diaries shows there are so many pitfalls and traps that would be all too easy to fall into; enough to put people off the whole idea! The answer is simply to learn about the subject before seriously jumping in with both feet. Clearly it adds a whole new layer to all parts of the scene-to-screen chain. In each link there are traps to avoid, and avoid them you must, because getting it wrong produces unwatchable results.

That’s enough gloom! And in any case, there is a growing army of 3D-capable professionals to make sure things work well every step of the way. Even so, it would be sensible to know for yourself how things should be done, so welcome to Part Three 3D Diaries! We know that television is an illusion that works very well and is accepted by our perception. Stereo 3D makes all those calls on our brain and then a whole lot more. It is an even bigger illusion that can work well so long as the material is presented correctly. Go outside the rules and the illusion is instantly shattered.

Rewind not many years and nearly all 3D production was on film and, typically, many months were spent just correcting the mismatches of the left and right cameras. Today television is already able to make a good job of live 3D coverage, meaning that ‘mismatch’ errors are corrected, or avoided, on the fly. But for non-live productions the camera mismatches will be left for correcting in post. In truth, this allows time for more accuracy and adjustment of 3D for dramatic effect and should produce the best possible result.

Knowledge and the right equipment are needed to succeed. For the first part, here are some useful tips.

Shoot it right. All 3D post people agree that this is the number-one priority. Conversely, aiming for ‘fix it in post’, as you might in 2D, is the absolutely wrong approach for 3D. That third dimension can describe a hole so deep that you may never get out of! It’s true there are some 3D issues that can be fixed in post but be very sure exactly what these are and go no further. Finding out the rights and wrongs requires the knowledge of a 3D expert and they are still relatively thin on the ground; but the good news is that their number is growing fast.

3D quality. You really must know the quality of the 3D in the footage you are committing to post produce; otherwise you could be landed with endless hours of corrective 3D work that you had not allowed for, and so could be seriously out of pocket. In practise you can check the quality by having that rare knowledgeable 3D specialist monitoring the shoots on-set, or by carefully analysing the recorded in footage in 3D before quoting for the job.

Allow plenty of time. Even well shot 3D takes longer in post than 2D and, obviously, also depends on the two points above.

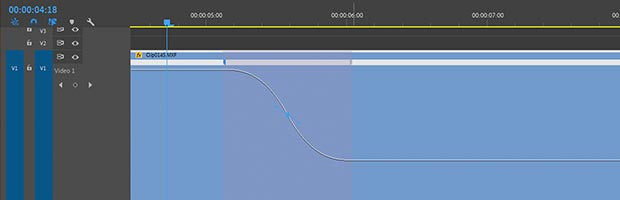

Offline and S-3D grammar. If the offline was run from one camera ‘eye’ then the resulting EDL could, and almost certainly would, break the rule of S-3D grammar that says, ‘avoid cutting between large changes in convergence’. Breaking the rule creates an unnatural situation and is uncomfortable to watch. Another rule says that there should not be as many cuts (as 2D). This is because our brains have to work out the 3D information of each one, and fast cutting is really bad as we cannot keep up. These rules are important – as I know to my cost after one visit to a 3D cinema!

Another weakness of one-eyed offine is that there could be glaring differences between left and right footage, such as lens flares, highlights and reflections that affect each eye differently. Also footage from Mirror rigs produces slightly different coloured images for left and right, so again this could not be checked. Some 3D post packages, such as Quantel’s Pablo, have extensive 3D tools to provide quick fixes for such disparities, which saves time by not having to off-load the footage to another area for correction.

Obey the 3D rules. This could be a book but here are two things that many get wrong; understanding the limits of disparity and mixing up depth cues. Disparity is what you see when you take your 3D glasses off – the double image showing the different left end right-eye horizontal positions of an object. The bigger it is, the greater the depth. Its value depends on variables including lenses, inter-axial distance (between lenses), convergence and the range of depth within the scene. Beyond a certain limit, viewers have trouble accepting the image (headache!). Measuring and managing disparity is a key concern for both stereographers and post finishers. This is where high-level tools such, as Mistika, come in with disparity mapping through a scene and changing its values in various zones.

Depth cues are what your brain latches onto to create a stereoscopic impression of a scene. There are several, but they all need to agree with each other, otherwise stereopsis, our 3D perception process, fails (headache!). So placing a title optically in front of an object, but stereoscopically behind it means your brain accepts the title is in front of the object because it is occluded by the title, while stereopsis says it is behind the object. The result is a title that is strangely but powerfully difficult to read!

Size (of viewing screen) matters. Another behind-infront conflict is created when objects come out of the screen and are cropped by the screen edge, or when an object moves off the edge of the screen. In either case there will be an anomaly where parts of, or the whole, object exists in one eye but not in the other. This is more noticeable on small TV screens where the viewing angle is relatively small, whereas cinema screens should look better as the pictures edges are further away from our centre of vision.

Equipment

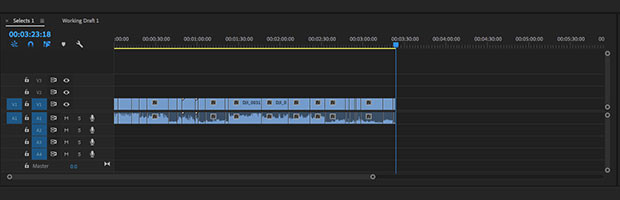

Get a 3D editing system. It might be possible to get a 3D upgrade to a 2D system; otherwise you really need a new one. Making 3D work properly means getting everything right and this makes a strong case for the all-in-one-box approach to editing and post where all the elements can be assembled, viewed and adjusted in one place.

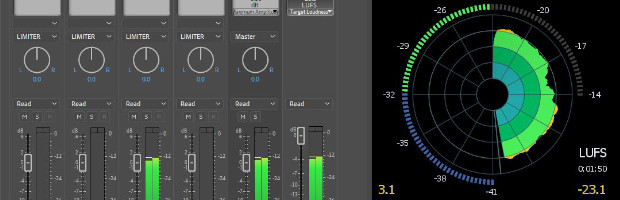

Video quality. It’s best to have two in-sync real-time full resolution video channels as then you can see all the problems that need fixing, such as left-right sync issues (the quickest way to induce a headache!) and checking the pace and convergence ‘depth’ over edits. Accessing and processing two streams of 2K, or even 4K in real time requires a powerful ‘post engine’ but it can avoid rendering time that otherwise slows the whole process. Using low resolution images is a compromise that can spoil the 3D perception, or rather illusion, as for example, ‘screen effects’ such as aliasing and lens flares, look weird because they have no reason to be there in 3D.

View in 3D. For finishing you need to watch in 3D as this is what the end product is. Also left and right streams from digital cameras are almost never correct, with issues of geometry, lens inaccuracies, convergence adjustments and colour balance, and it’s hard to deal with these viewing just one channel. Also checking depth continuity can only be done in 3D.

All of the above has little or nothing to do with 2D post, which has not been mentioned as it is taken for granted. 3D editing, grading and other post activities mentioned are all supplementary to 2D. So now, perhaps, it is easier to understand exactly why ‘fix it in post’ could easily go seriously wrong in 3D. Don’t go there.

Writing 3D Diaries has given me the excuse tap the knowledge of manufacturers and industry experts. This article owes much to the help given by Roger Thornton at Quantel and David Cox, a 3D post specialist.